Your Free e-book

Feedback – The game changer for performance management!

Introduction

Let’s face it, ditching the annual appraisal is now old news, most of us know and accept that the key to success is through a series of performance conversations throughout the year rather than a once or twice yearly appraisal, but how do we make moving to ongoing performance management more of a reality?

It is generally accepted that goal or objective setting is fundamental to establishing a high-performance culture, however without an understanding of our progress against these goals, we don’t know which behaviours to adjust or repeat to maximise success. The missing ingredient is feedback – the key to delivering sustainable high performance.

Organisations that recognise this and put feedback at the centre of their performance management processes are likely to be better able to flex and respond to ever-changing circumstances. They are more likely to learn from successes and failures, delivering continuous improvement and increasing their competitive advantage. In addition, staff who receive regular developmental feedback and coaching feel listened to and believe they have access to opportunities that enable them to develop and grow, increasing engagement and the retention of talent (Mone & London, 2009).

There are many different forms of feedback: verbal feedback; behavioural feedback; performance ratings and 360° feedback and they should all play different roles within your performance management process. These different types of feedback should be approached with caution as some can be risky or even counter-productive if positioned poorly or managed badly. This can create a culture of fear around giving or receiving feedback or in some cases a complete absence of feedback or feedback ‘vacuum’. If either of these are true for your organisation, then it is highly likely to be holding your performance and culture back.

This e-book explains how you can successfully put feedback at th e centre of your performance management cycle. It considers the various types of feedback, the pros and cons of each and explains how to position them for best effect. By drawing on neuroscience and recent psychological research, we are also able to make evidence based recommendations and provide practical tips that you can take back and apply to your own workplace.

In Chapter One we consider what feedback is; the different types of feedback that occur in the workplace; why it is so important for learning and growth and the business benefits of feedback done well.

Chapter Two looks at the practicalities of good feedback; the interplay with neuroscience and provides real examples of effective feedback.

In Chapter Three we look at the critical role that feedback plays within Continuous Performance Management and then move on to dedicate Chapters Four and Five to feedback via performance ratings and 360° feedback looking at how you can minimise risk and utilise both of these tools effectively within your organisation.

Find out more

Understand how Actus Performance Management Software can support your organisation.

What is feedback?

Feedback can be defined as a return of information relating to the output or impact of a process or activity. In our bodies, autonomic feedback mechanisms are essential to our survival as they manage circulation, temperature regulation and many other functions. In our homes we probably have temperature controls that adjust the room temperature in line with feedback from a thermostat. Even the way we interact online provides feedback on our preferences or behaviours which is then used by search engines or advertisers to adjust the information that they provide us with, whether we like it or not!

In the workplace, there are different types of feedback, all of which can be aligned positively to your performance management processes (this is explained in detail in Chapter three). In this e-book we will consider the following types of feedback, commonly used in the workplace. Feedback may be positive or developmental; verbal or written and qualitative (descriptive) or quantitative (numeric or including ratings):

- Performance feedback – should be aligned to key performance measures or goals.

- Behavioural feedback – aligned to behaviours, ideally pre-defined in a competency or values framework.

The above types of feedback can be delivered one-to-one; manager to individual; peer-to-peer or multi-source e.g. 360° or 180° feedback. Feedback can even be individual via personal reflection. As technology progresses, non-verbal feedback sources are likely to increase and new forms of feedback may emerge.

What is the impact of feedback?

The most authoritative study to date about the impact of feedback comes from a meta-analysis that included more than 23,000 instances of feedback (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). Surprisingly they found that although overall feedback had a moderate-sized positive impact on performance, it was just as likely to decrease performance or remain the same. This is somewhat concerning if the purpose of the feedback is to improve performance!

However, these studies included a very high level of variability in the type and quality of feedback; a meta-analysis is a retrospective analysis of a number of other studies which will have been focused on slightly different outcomes and will have been conducted under differing conditions. Therefore, it seems logical that if inconsistent feedback can deliver moderately positive results, then improving the quality and consistency of workplace feedback is likely to deliver more consistent positive results and this is a topic worth serious focus.

This is supported by other studies as it has been argued that feedback is among the most critical influences on learning, (Hattie & Timperley, 2007) as long as it is done well. When it comes to managing performance effectively, research consistently shows that goal setting (Locke & Latham, 1991) combined with regular feedback are the two most effective ways of maximising individual and organisational performance.

Other studies give us improved clarity on what type of feedback is most likely to improve performance. In the case of peer or 360° feedback it seems that performance improvement is most likely to occur when the feedback giver indicates explicitly that change is necessary so that people perceive an actual need to change their behaviour (Smither, et al., 2005). This is an interesting learning point for organisations when training managers to deliver feedback, are they being explicit enough about any changes that are required? If the message isn’t clear or perhaps even overt then the effectiveness of the feedback seems to be reduced.

The same research showed that other factors that make a difference to performance improvement are related to the inclination of the recipient, both towards the feedback giver and towards feedback in general. For example, do they have a positive feedback orientation, react positively to the feedback and/or believe change is feasible? Are they prepared to set appropriate goals to regulate their behaviour, and take actions that lead to skill and performance improvement? Do they trust and/or respect the feedback giver?

Clearly, the inclination of the individual is also likely to be affected by cultural factors like their previous experience of feedback, if they have had a bad experience in the past they may have developed a protection mechanism and rebuff feedback. One final contributing factor is likely to be the ability of the manager or feedback giver to act as a coach, using effective questioning and listening skills, along with empathy to help the individual to buy into the change and set goals and actions. The importance of both these points are covered later.

What business benefits can feedback bring?

Tom Rath and Donald Clifton of Gallup surveyed more than 15 million employees worldwide on the concept of feedback in the form of recognition and praise (Rath.T; Clifton.D., 2007). They found that individuals who received regular recognition and praise were more likely to:

- Increase their individual productivity

- Increase engagement among their colleagues

- Stay with their organisation

- Receive higher loyalty and satisfaction scores from customers

- Have better safety records and fewer accidents on the job

In fact there is also evidence to suggest that employee health and wellbeing can be directly affected by the relationship that they have with their line manager. So, it seems that if we were to replace the ‘feedback vacuum’ with regular recognition and praise then this would be a good place to start and the benefits can be far reaching, benefiting the individual just as much as the organisation.

However, it isn’t just praise that has been shown to improve performance. A large scale meta-analysis by (Pritchard, et al., 2008) found that using performance measures like KPI’s or objectives and then assessing these using specific feedback measures resulted in tangible business benefits. Examples of performance measures ranged from specific productivity or first-time fix targets to customer service ratings or being seen to demonstrate specific behaviours consistently. The results included large productivity improvements that were shown to last over time and in some cases years. Importantly these improvements were consistent in many different types of settings (i.e., type of organisation, type of work, type of worker, country) which means we can be confident that embedding a process of setting performance objectives and giving feedback on performance against these is highly likely to result in positive outcomes for our organisation.

When and why does feedback go wrong?

Neuroscience may provide part of the answer to this as it seems that the very words ‘I would like to give you some feedback’ actually provoke the fight or flight response in our brains; essentially we automatically consider this to be a threat and brace ourselves accordingly. Psychologist Rick Hanson states that:

“The mind is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones”

Additionally, it seems that we are conditioned to seek out 3-5 times more negative feedback than positive which suggests that when we receive feedback we may focus in on the negatives and take these out of context. Of course, if the feedback giver has a difficult experience providing feedback, then they are less inclined to do this again and a vicious cycle ensues.

Other problems can arise when there is a lack of trust or respect between both parties, as feedback may not be seen as being accurate or trustworthy if we consider that someone has some sort of personal agenda.

“An employee who does not trust the “provider” of feedback may not internalise feedback and will most likely just shrug off the comments and continue their business as usual.”

Equally problematic is the style of feedback given; general, non-specific feedback or hearsay is more likely to arise suspicion or confusion than a positive change in behaviour.

Perhaps, because of these difficulties many of us have got used to operating in an absence of feedback in the modern workplace. Many performance issues are left to get out of control and could have been nipped in the bud earlier had the manager been trained to be courageous enough to address an issue directly using high-quality feedback.

If we return to the fight or flight concept, all too often, giving or receiving feedback feels like conflict and most of us try to avoid conflict. But working in a feedback vacuum definitely isn’t the answer either, how else do we understand what we are doing well or could do better? How do we avoid repeating mistakes or emulate other people’s successes? How else do we gain the potential productivity and performance improvements that are possible through well executed feedback?

We simply need to learn how to do it better and more often!

Discover more

Download free HR and Performance Management Resources.

What does good feedback look like?

It seems that we should look to positive psychology if we are to improve the way we do feedback and this may mean reversing our inherent programming to seek out the negatives first. Don Clifton, who is known by the American Psychological Society as the ‘Grandfather of Positive Psychology’ stated:

“It isn’t until people know what makes them talented and unique that they know how to perform better in their job”.

This concept of looking to strengths first also resonates with the findings within the recent CIPD research report “Could do better – Assessing what works in performance management” where they looked at strengths based approaches to coaching and feedback during performance management conversations (Gifford, J, 2016). The conclusion was that managers who took on a coaching style i.e. more questioning and listening than ‘tell’ combined with strengths focused and forward looking performance conversation could have a significant increase on perceived performance. A ‘feedforward’ technique like this should be about eliciting positive experiences or strengths and focusing on how these can be enhanced or built on moving forwards. So, following a work presentation a manager might sit down and help their staff member to reflect by focusing on what worked or what went particularly well during the presentation. They may ask the individual to consider what they would repeat if they were to do it again. This switch in emphasis can feel alien to many of us as we are all so used to focusing on what went wrong.

A more positive approach doesn’t mean ignoring things that can be improved but the emphasis should be more about focusing on what is working. It is easy to see how this technique could be used to good effect during 121’s or appraisal conversations and could well revolutionise their effectiveness.

Consider how you can put in place simple recognition schemes that can be used by all staff to notice and recognise high performance. If you have organisational values, this is a great way of bringing these to life as people can consider these definitions and recognise others against them.

Some organisations do this effectively through providing themed postcards or stickers where people can choose a specific postcard and recognise a colleague using these. Others are able to do this by colleague of the month type incentives which may be voted for by others or ‘Champion’ awards. The important point here is that these are little and often, creating a culture where people become more acclimatised to giving and receiving feedback and find it less threatening.

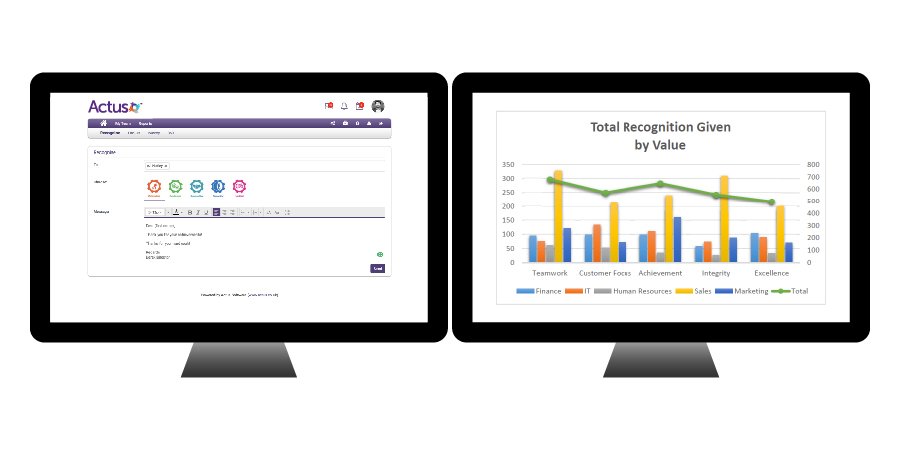

If you use performance management software like Actus you can encourage these more positive behaviours using the recognition module which encourages ongoing feedback and recognition between colleagues. It also makes this visible at appraisal or development time. Additionally, the automated reporting gives you greater visibility at an organisational level which creates a greater understanding of where the more engaging management behaviours are sitting.

What to avoid when giving feedback

Some of us will remember receiving feedback from school or parents like “You must try harder” or “Well I guess that will have to do” or even “Good job!”. All of these examples are very non-specific or general and it is very difficult to understand what we need to improve or even what we did well. We may also have experienced feedback that felt particularly personal such as “You are never going to be any good at maths/running/languages” or “You are a very bad/good/naughty girl/boy” Why does this type of feedback provoke such a strong emotional reaction?

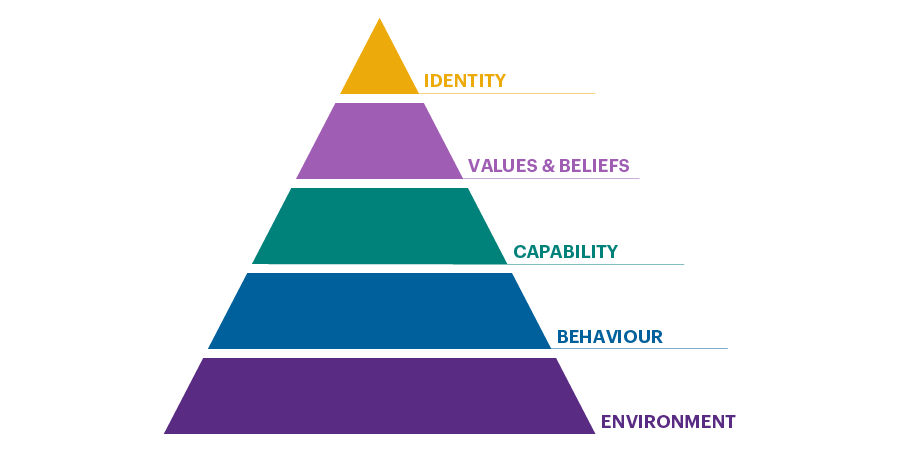

The model of Logical Levels first outlined by Robert Dilts in his book Changing Beliefs with NLP and based on NeuroLinguistic theory is helpful to explain this (Dilts.R, 1990). He noticed that people responded more strongly to certain types of negative statements made about them by others even though the subject matters was essentially the same. He used the following example to explain this:

- That object in your environment is dangerous.

- Your actions in that particular context were dangerous.

- Your inability to make effective judgments is dangerous.

- Your beliefs and values are dangerous.

- You are a dangerous person.

The judgment being made in each case is about something being “dangerous” but most people feel that each statement is increasingly emotive. For someone to tell you that some specific behavioural response made was dangerous feels quite different to them telling you that you are a “dangerous person.” Dilts found that by choosing the same subject or judgement and then applying language relating to environment, behaviour, capabilities, beliefs and values and identity, people would feel progressively more offended or complimented, depending on the positive or negative nature of the judgment.

If we apply this to feedback and imagine someone was saying each of the following statements to us, it feels like they are climbing the levels of this pyramid with each statement feeling increasingly more intense or personal.

- Your surroundings are (stupid/ugly/exceptional/beautiful).

- The way you behaved in that particular situation was (stupid/ugly/exceptional/beautiful).

- You really have the capability to be (stupid/ugly/exceptional/beautiful).

- What you believe and value is (stupid/ugly/exceptional/beautiful).

- You are (stupid/ugly/exceptional/beautiful).

Again, notice that the evaluations asserted by each statement are the same. What changes is the aspect of the person to which the statement is referring.

Unfortunately, statements like this may come out of our mouths without us even considering it to be feedback. If we are in a position of trust e.g. a parent, one of the worst things we can do is make negative comments/give feedback at the capability level or higher to young children as it is thought that they do not have the ability to reject them under the age of about 7 years old. Therefore, throwaway statements like “You are a bad girl/boy” or “You are hopeless at maths” could be internalised as factual and carried through into adulthood.

In most adults, if negative feedback is aimed at the identity, beliefs or capability level then at best it will make the person defensive or to want to prove you wrong and at the worst it may demotivate them and lower their self-esteem or increase their stress levels. However, it really is worth us becoming more aware about the potential impact of what we say to be sure that it has the impact that we intended.

How to deliver feedback well

The following structure for giving feedback is used to good effect throughout the management programme of a Global Engineering Firm that we work with:

- Describe the specific behaviour without value judgement e.g. I noticed/I heard/When you said.

- Explain the impact of the behaviour and take ownership of the impact yourself, if possible e.g. I felt/I thought.

- Make a recommendation e.g. ‘Next time you may want to’ or ‘Keep on doing that it works for you!’.

Good quality feedback needs to be specific and factual rather than general and personal. An example of specific, factual feedback following the above structure might be “I noticed when you delivered the presentation that you made eye contact throughout with the audience and I could hear you clearly at the back of the room.” Both of these points are stating behavioural facts from the feedback giver’s perspective without value judgements such as it was ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

Ideally feedback should be overwhelmingly specific with a balance of positive and developmental pointers. General Positive Feedback is acceptable in smaller quantities whereas General Developmental (negative) Feedback should be avoided.

It is then really helpful to explain the impact of those facts (which could be considered to be more subjective) so in this example might be “which made you appear confident and professional” then the recommendation “keep this approach going as it definitely works for you”. It is surprising how difficult many people find this to do because we are so used to general, non-specific feedback laden with opinions and value judgements.

Delivering good quality feedback regularly using the structure above is a skill worth developing for us both professionally and personally. Remember, we should be aiming for three to five times as many positive instances of feedback to one of developmental or critical because we are preconditioned to focus on the negatives and deflect positive. In the words of the One Minute Manager by Ken Blanchard we need to make the effort to “Catch people doing things right!” however, sometimes that is easier said than done (Blanchard.K & Johnson.S, 2015).

A senior manager who created this habit successfully by putting three paperclips into one pocket at the start of the day and every time she delivered some positive feedback she moved one paperclip over into the other pocket. It gave her a tangible reminder throughout the day to look out for things that people were doing well and to give feedback on them. Of course, this is only effective if the feedback is sincere, otherwise it will be counterproductive.

Another well-meaning business targeted every manager to give five pieces of positive feedback each day. Unfortunately, the quality and sincerity wasn’t there and individuals became suspicious about any positive feedback they received, exactly the opposite effect to the intention!

In summary we know that good quality feedback is in short supply and that the impact of feedback can be dramatically different based on the language or logical level that it is aimed at. We know that good, quality feedback is specific and behavioural and that we need to create the habit of delivering greater quality, positive feedback on a day-to-day basis to build our own capability and reduce the tendency for people to focus on the negatives.

Download PDF

Click here to download the PDF version of the e-book.

How does feedback fit within Continuous Performance Management?

We mentioned earlier that goal setting and feedback are at the centre of what drives high performance and therefore a good performance management process should incorporate this.

A lot has been published in recent years about moving from once yearly appraisal processes to a more continuous performance management cycle, and feedback is core to making this work well. Whether this is something new or not is perhaps up for debate as most annual appraisal processes should also be supported by regular 1 to 1 meetings between manager and employee when feedback on performance is discussed. The research has long indicated that besides formal appraisals (which happen once or twice a year) informal appraisals and feedback must be a part of the system and the frequency of feedback should be increased (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996).

Continuous performance management is arguably little more than a spin on this approach with regular ‘Check-ins’ becoming the term for a quarterly or 6 weekly performance review. The important principle to keep in mind is the fact that regular goal setting and review or feedback has been shown to positively impact performance as long as the quality of the relationship between the manager and employee is constructive and the feedback deemed fair.

Clearly performance management processes vary from one organisation to another but they all tend to incorporate the same activities.

If we take the Actus visual example below of a continuous performance cycle, we can consider how different types of feedback would fit in at each stage.

At the start of the year it is important to set SMART performance objectives so that the individual has clarity about what is expected in the first place. In line with continuous performance management principles it is particularly helpful if the objective can be broken down into milestones so that it can be reviewed on an ongoing basis. Verbal, written or rated feedback can then be applied to the objectives or milestones throughout the year during 1 to 1’s and informal conversations. If feedback is documented using a system like Actus, it is possible to track progress and encourage maximum performance by using the feedback to motivate, refocus and recognise performance throughout the year and because it is already documented, this saves time at year end.

The Actus model has separated out performance feedback from developmental feedback, with traditional performance feedback taking place during the mid and end of year appraisals. The developmental feedback takes place during the development review and career conversations. Both types of feedback can take place during 1 to 1’s although it is probably best not to mix them in the same meeting if possible. This is recommended because studies indicate that managers are likely to rate differently depending on the perceived purpose (Jawahar & Williams, 1997).

If ratings form part of your process, they can be applied to individual objectives or to overall performance during appraisal. The mid-year point is a very important part of the cycle where formal feedback should be documented. This is a great opportunity for the manager and employee to ensure that they are both viewing progress against performance in the same way. If ratings are to result in reward at the year end, it is strongly recommended that the employee receives feedback and an indicative rating at this stage to ensure that they understand how their performance to date is being perceived. This gives the staff member time to improve performance and subsequently their end of year rating, if needed, hopefully avoiding any nasty surprises at year end.

Dividing the year up like this takes the content of a traditional (and lengthy) end of year appraisal and distributes it throughout the year giving each quarter a distinct focus. It provides a pragmatic approach to embedding continuous performance management with the following additional benefits:

- Discussing development requirements at the end of Quarter 1 makes it possible to address gaps sooner which could improve within that year, rather than waiting until the end of the year to discuss development needs when it may be too late.

- Disconnecting performance ratings from talent management conversations should lead to more honest conversations. It also removes the tension as staff are likely to be more receptive to developmental feedback as they are not nervously waiting to fight their corner for a particular performance rating.

- Providing additional opportunities for positive feedback throughout the year as much as possible using recognition schemes.

- Finally, by having conversations all year round and documenting them, it reduces the duration of the end of year appraisal as much of the preparation is done and should improve the quality as the focus is less on ticking boxes and more on quality conversation – which is ultimately what we are after.

Find out more

Understand how Actus Performance Management Software can support your organisation.

Performance ratings as feedback

Rating behaviours or performance is relatively common as part of performance management processes or 360° feedback. Ratings are a very clear way of providing feedback and can be a really helpful way of both parties achieving clarity about existing or expected performance, it is however also fraught with risks of perceived unfairness.

Without manager training and/or some kind of moderation it is very difficult for ratings to be applied consistently across an organisation. If these unmoderated ratings lead to financial consequences, there is likely to be a significant amount of cynicism and negativity which could make a performance related pay scheme counterproductive. As mentioned in the previous chapter, studies have shown that managers are likely to rate performance differently depending on the perceived purpose (Jawahar & Williams, 1997). Managers providing ratings for salary or promotion purposes tend to be more generous and less accurate than when they are rating for development purposes. These inconsistencies could have any number of causes including trying not to disadvantage someone financially; fear of the conflict associated with giving someone negative feedback or trying to motivate an underperformer. Our recommendation would be to split out developmental and performance ratings as much as possible to reduce this potential bias.

Such issues may be even more pronounced when peer-to-peer ratings are used as part of the end of year appraisal process, particularly if they are non-anonymised. Over-rating is common in this situation probably because peers do not want to be seen to be negative about their colleagues, particularly if it will affect their pay. Another less altruistic reason is the sheer hassle factor or the very common wish to avoid conflict. Let’s say they are honest and mark a colleague down on a behaviour, then the odds are that HR or the colleague will want to gain more insight and ask them for more examples. You can see why this kind of system may lead to strategic overrating of colleagues so that their scores don’t stand out and they are not asked to explain them.

These points demonstrate how important it is that we are aware of these potential biases when designing our performance management process, particularly if we are including feedback that links to pay. We must also adequately train our HR colleagues and performance raters to be consistent and expose them to the experience of having their scores moderated if the process is to be deemed fair (Lawler.E & McDermott.M, 2003). Without these safeguards in place, there is a high-risk that the whole process will be counterproductive.

How to manage ratings positively within your performance management cycle

Despite the potential challenges, there are a number of ways in which you can utilise ratings within your performance management processes, in order to make it work well for you. These have been summarised below:

- Define standardised rating with specific behavioural examples.

- Train your raters.

- Moderate ratings that impact reward.

1. Standardised ratings with specific behavioural examples

If you use a competency framework then it is important to ensure it is well-defined with specific examples of behaviours that meet, exceed or fall short of expectations. If there are multiple behavioural definitions for a specific level of competency, define the number and frequency of times that these behaviours should be demonstrated for the individual to be considered to be meeting this particular level. To illustrate this we have taken an example from a Customer Orientation Competency below, which has a number of levels designed to give typical examples of observable behaviours.

Level 2: Tailors responses to meet the customers stated needs

- Actions and decisions demonstrate an understanding of customer expectations.

- Relates easily to the customer using language the customer will understand.

- Asks questions to check own understanding of the customer’s request.

- Takes personal ownership and responsibility for following up enquiries and requests.

Then to ensure consistency, the ratings themselves should be clearly defined, including the frequency and consistency of the desired behaviours for additional clarity:

- Demonstrates behaviours consistently: Consistently demonstrates all the behaviours positively.

- Usually demonstrates behaviours: Usually demonstrates most of the behaviours positively.

- Partially demonstrates behaviours: Demonstrates some of the behaviours, some of the time.

- Rarely demonstrates behaviours: Rarely demonstrates these behaviours or shows negative behaviours in this area.

2. Train your feedback givers

Giving quality feedback is not a skill we are born with and we know that at least a third of managers in the workplace today have never received any formal management training (CIPD, 2013).

Thus, an organisation can have all the right systems and procedures in place with regards to performance management but none of this will matter if the line managers are not sufficiently well trained or engaged in the process (Singh, 2012). Additionally, managers may never have experienced any role modelling of quality and the same research shows that 48% of managers are likely to have been promoted based on their performance rather than their people management skills. Clearly, training and education has to be seen as a priority.

It isn’t just feedback that managers or feedback givers need to be trained in. There are a range of associated management skills that need to be developed alongside this. These include the ability to set clear objectives or expectations, coaching and having ‘courageous’ conversations, as many performance issues arise from a lack of clarity around expectations in the first place. If individuals don’t have clear SMART objectives agreed from the outset, it is very difficult for feedback on performance to be anything but subjective. The same goes for behaviours or competencies, if they are vaguely defined then there is an opportunity for feedback to be misinterpreted. However, if there are clearly understood expectations, the individual is able to reflect on their own performance – effectively provide self-feedback which is likely to result in a much more constructive conversation at appraisal time.

3. Moderate ratings that result in reward

We learnt earlier that managers are likely to adapt their ratings depending on the perceived impact and are more likely to overrate performance that is linked to reward. Of course, this is likely to result in an overall inflation in ratings and the purpose of a performance related pay scheme could therefore be lost. Introducing a formal moderation or calibration process can make a huge difference here as raters are required to explain their rationale for a specific rating. This is hugely educational for raters if managed correctly. Usually, a group of peers are invited to join a meeting which is facilitated by someone neutral, typically from HR. All of their direct reports proposed scores are shared with the group and managers are invited to provide evidence to support the rating that they have proposed for an individual. Colleagues may offer examples in support of these ratings or may challenge them, a debate is facilitated and a final ‘moderated’ score is agreed which will relate to pay. The first time a manager goes through this experience is often highly educational as the quality of their behavioural examples or evidence is scrutinised by their peers and they can be exposed if unprepared. If you are linking ratings to reward, it is a good idea to take managers through a mock moderation session first as it is very likely to motivate them to work harder on the quality of their behavioural examples and evidence in future!

Development from this experience is threefold, firstly they gain feedback from their peers as to whether the individual in question is viewed in the same way that they view them, secondly they will understand whether the quality of their evidence or feedback on the individual in question is objective and compelling and finally they will gain insight into how their peers apply their own ratings to other staff members.

Rating behaviours or performance shouldn’t be something people shy away from because it can bring real clarity to a performance conversation and gives a tangible measure for development or reward. They can increase objectivity and perceived fairness. However, ratings can also lead to people ‘gaming’ the system or if the meeting becomes purely focused on the ratings, they may forget that the primary purpose of the appraisal was to have an engaging and constructive conversation. Ratings can be tremendously useful, but require a strong lead from HR if they are to be managed and used well.

Discover more

Download free HR and Performance Management Resources.

The Pro’s and Con’s of 360° feedback

Having looked at feedback in relation to the traditional performance management cycle it is now time to consider how 360° feedback best fits in. In the previous chapter we explained the risks of bias in relation to manager or peer feedback and these can still apply to 360°feedback.

Unfortunately, it seems that many organisations consider this kind of feedback to be a panacea when, in reality it can be the opposite if introduced into a culture that isn’t ready. That said, 360° feedback can also be an incredibly enlightening development tool, if used in the right way.

What is 360° feedback?

It is the process of obtaining feedback from a variety of sources, usually upward (from the line manager), downwards (from direct reports) and sideways (from peers) hence the term 360° as feedback is being obtained from all around. Feedback can also be obtained feedback from external clients or other stakeholders. 180° feedback is similar to 360° feedback in many ways but tends to just involve direct reports giving feedback on a boss, so it can also be known as upward feedback. Like 360° feedback it is very helpful if the debrief is professionally facilitated.

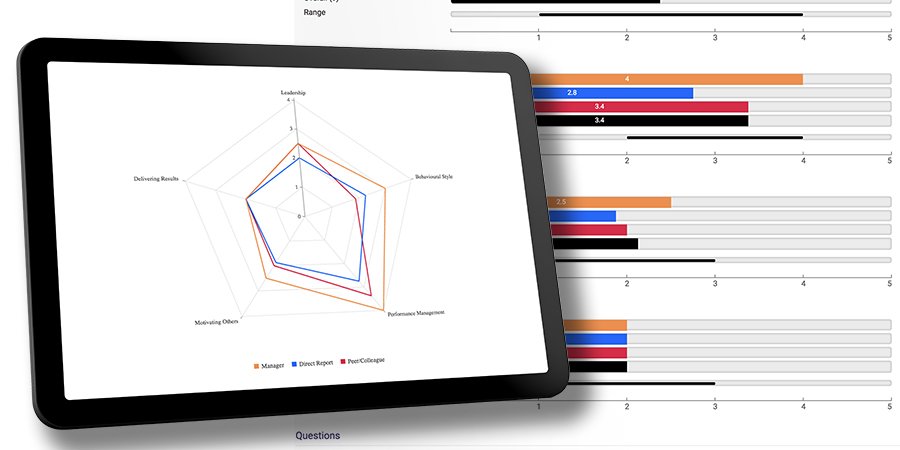

In both cases, a set of questions are established which are then addressed electronically to each of the feedback sources e.g. “How effective is X at meeting deadlines”. Respondents then answer against a scale ranking the extent to which they agree or disagree with this statement; commonly 1-5 or 1-6 which may equate to ‘Not at all’ to ‘Always’ or ‘Consistently’. Results can then be collated into bar charts or similar giving visibility between relative differences of opinion between one group of respondents and another. Usually there will be a high-level summary like the spidergraph image above and then a more detailed break down like the bar chart further down.

A point to note is that it is good practice to ensure that raters are anonymised by only showing scores with a minimum of three responses, preferably more. This is with the exception of the line manager, whose scores are usually directly attributable as they have their own bar. This is because the line manager should be able to justify their view face-to-face in order to develop the individual without hiding behind others.

When does 360° work well?

We believe that 360° feedback can be incredibly valuable but needs careful handling. It can be a valuable developmental tool for developing self-awareness. Generally, when we start out in the workplace we see things from our own perspective and have little understanding of how our actions are viewed by others. So, a very confident, outspoken 20 something could be seen as pushy and arrogant by some, ultimately this could hamper their career prospects if they are unable to moderate their behaviour in certain situations. Receiving constructive behavioural feedback, particularly if there are consistent themes across respondents gives them the self-awareness to choose to adjust this behaviour and perceptions should they wish. This can be a powerful, positive experience if handled well, usually by a neutral, experienced facilitator in a safe, developmental context.

Another great use of 360° is as part of management or leadership training or as part of an executive coaching programme. Again, this is because any development insights can be captured as part of a training or coaching plan for the individual to work on. By repeating the process 18 months to two years later, the individual can see how they have progressed (hopefully). In fact, using a 360° tool at the beginning and end of a development programme can be a helpful way of showing impact and potential return on investment for training and development.

360° feedback can also highlight differences in perception between different groups of people and may provide useful evidence for an individual who feels their manager’s opinion of them does not reflect that of others.

Common pitfalls to avoid with 360° feedback

The challenge with 360° feedback is that it is generally communicated in writing and can take some interpretation. Unlike verbal feedback, you cannot ask for clarification or further examples to better understand it. The best tools require respondents to provide some written commentary to expand on their ratings as this tends to give context for the respondent. However, the quality of written commentary from others can vary according to the levels of trust within a culture so having a neutral coach to support the interpretation of a report is essential.

Just because you are gathering feedback from many, does not automatically mean that the results are without bias. It could be less accurate using 360° or peer feedback to generate ratings that link to reward than ensuring that line managers have the skills and capability to manage performance directly.

Consider the maturity of your organisation/business. Do people trust that any feedback that they give about someone will be treated anonymously? If you are rolling out a programme of 360° within an organisation it is worth ensuring that potential respondents understand the following as it can make a big difference:

- Line managers can be identified so should be aware of the impact of very high or low ratings, especially when directly compared to others.

- Be honest, but constructive and give examples if possible.

- Written feedback to explain ratings is extremely valuable and should be as specific/detailed as possible.

360° feedback is a really useful development tool when it is used in a safe environment and the individual is given coaching or support to interpret the findings and decide if/how they want to use them. It works particularly well when the individual is given a personalised feedback session with a neutral coach (not someone who has contributed to the feedback) and the individual feels comfortable enough to explore how they perceive their own behaviours compared to others.

It is to be encouraged, if used as a developmental tool but to deliver it well requires investment in time and money, educating the organisation how to deliver quality feedback and doing 1 to 1 feedback sessions. Ideally 360° fits within a leadership development or coaching programme and there should be an ongoing commitment to it – perhaps every two years to show progress.

So 360° feedback is a great option if your organisation is committed and skilled to making the most out of it. It is, however quite sophisticated and you need to ensure that your culture is ready for it as it is not a panacea or a quick fix.

Most businesses that we talk to who think they need 360° actually need to start with embedding the basics as this would drive far faster and better results and would build a stronger foundation for 360° . If you can confidently answer yes to the following questions then it is probably a good option, if not then you may want to prioritise management development first:

- Are your managers consistently setting objectives at the start of the year and managing performance against them?

- Do you have a culture of open and honest feedback – both developmental and constructive criticism?

- Have you got a majority of experienced managers or if less experienced, they have received formal management training?

- Do you have a culture of openness and high trust where making mistakes is encouraged and it feels safe?

- Do you have someone with the time and experience to own the 360° process, deliver 1 to 1 feedback, keep it developmental/manage any fallout and basically to keep it positive?

Download PDF

Click here to download the PDF version of the e-book.

Conclusion

Feedback is a very powerful tool and organisations are increasingly keen to incorporate it into their performance management processes and systems in order to increase productivity and engagement and to enable fairer distribution of rewards. However, it should not be allowed to enable abdication of line management responsibility, for example by basing performance ratings purely on the views of others.

Embedding a culture of good feedback will require good process design and probably some investment in the development of managers and staff. If you have an approach based on complete anonymity or conversely complete transparency, make sure you consider the cultural ramifications of this and whether they are conducive to the culture you want. Anonymity can encourage people to say things they may not say to people’s faces by being unnecessarily blunt or downright unpleasant causing untold damage. Complete transparency on the other hand can encourage the opposite approach, with people choosing innocuous or bland comments for the sake of an easy life to avoid having to answer follow up questions or getting into conflict.

Feedback comes in many formats and there can be a temptation to choose the wrong format for the situation, online feedback for example should never become a substitute for real time conversations and in the moment feedback by an eye witness. 360 feedback is a widely misused term and is probably still best used as a developmental coaching tool rather than a performance assessment measure.

Online feedback tools like those provided by Actus can support all types of feedback, whatever your approach and add tremendous value to the performance management process, allowing matrix organisations to gather feedback quickly and effectively across international borders, timelines and even from outside the organisation. They can hugely improve efficiency and objectivity, but such processes must be well managed to prevent badly written feedback being misinterpreted and potentially damaging. As HR professionals it is vitally important for us to understand and avoid the risks associated with poor feedback processes if we are to be sure that our feedback interventions and processes are positive and highly effective.

A performance management system like Actus can help to embed feedback as part of continuous performance management and separate out administrative and development feedback, as recommended by the CIPD to minimise bias. It also provides a cost-effective way of encouraging a culture of positive feedback and recognition and can incorporate 360° and 180° degree feedback making it a comprehensive and versatile solution.

For more information or a free demonstration just get in touch at info@actus.co.uk.

Find out more

Understand how Actus Performance Management Software can support your organisation.

Bibliography

- Blanchard.K & Johnson.S, 2015. The New One Minute Manager. s.l.:Harper; New Thorsons Classics.

- CIPD, 2013. Lack of management training causing culture problems, s.l.: People Management Newsdesk.

- Dilts.R, 1990. Changing Belief Systems with NLP. First ed. s.l.:Meta Publications.

- Gifford, J, 2016. Could do better? Assessing what works in performance management, s.l.: CIPD.

- Hanson, R., 2010. The Neuroscience of Happiness. Greater Good Magaazine, p. Online.

- Hattie, J. & Timperley, H., 2007. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Reaserach, pp. 77-81.

- Jawahar, I. & Williams, C., 1997. Where all the children are above average: The Performance Appraisal Purpose Effect. Personnel Psychology, 50(4), pp. 905-925.

- Kluger, A. & DeNisi, A., 1996. The effects of feedback interventions on performance. Psychological Bulletin, p. 119.

- Lawler.E & McDermott.M, 2003. Current Performance Management Practices. World at Work Journal, 12(2), pp. 49-60.

- Locke, E. & Latham, G., 1991. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 16(2), pp. 480-483.

- Mone, E. & London, M., 2009. Employee Engagement through effective performance management, New York: s.n.

- Pritchard, R. D., Harrell, M. M., DiazGranados, D. & Guzman, M. J., 2008. The productivity measurement and enhancement system: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3).

- Rath.T; Clifton.D., 2007. How full is your bucket?. 1st ed. s.l.:Gallup Press.

- Singh, A., 2012. Performance management system design, implementation and outcomes. South Asian Journal of Management, 19(2), pp. 99-120.

- Smither, J. W., London, M. & Reilly, R. R., 2005. Does performance improve following multisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis, and review of empirical findings.. Personnel Psychology, 58(2).